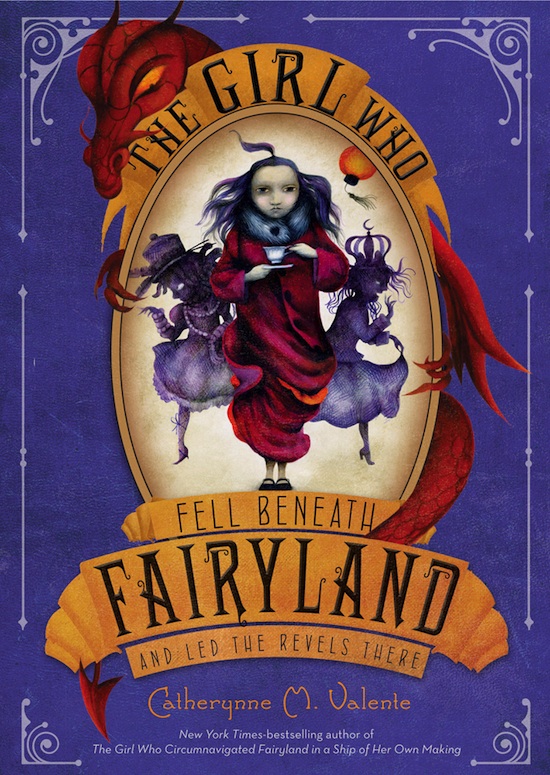

All this week we’re serializing the first five chapters of the long-awaited sequel to The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, Catherynne M. Valente’s first Fairyland book — The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There is out on October 2nd. You can keep track of all the chapters here.

September has longed to return to Fairyland after her first adventure there. And when she finally does, she learns that its inhabitants have been losing their shadows—and their magic—to the world of Fairyland Below. This underworld has a new ruler: Halloween, the Hollow Queen, who is September’s shadow. And Halloween does not want to give Fairyland’s shadows back.

Fans of Valente’s bestselling, first Fairyland book will revel in the lush setting, characters, and language of September’s journey, all brought to life by fine artist Ana Juan. Readers will also welcome back good friends Ell, the Wyverary, and the boy Saturday. But in Fairyland Below, even the best of friends aren’t always what they seem. . . .

CHAPTER V

YOU ARE FREE BEASTS

In Which September Leaves Fairyland-Above, Encounters an Old Friend, Learns a Bit of Local Politics, and Changes into Something Very Exciting, but Only Briefly

The stairway wound around and around. The wooden steps creaked beneath September’s feet. Several slats were missing, crumbled away with age and use. Just as her eyes adjusted to the total dark, little freckles of light spattered the gloom before her. As she went deeper, September saw that they were stars, small but bright, hanging like old lightbulbs from the stony ceiling, dangling on spangled, bristly cables. They lent a dim, fitful light, but no warmth. The bannisters of the staircase prickled with frost. September trailed her hand along the cave wall. I am not afraid, she reminded herself. Who knows what lies at the bottom of these steps? And just as she thought this, her idle hand found a smooth, slick handle set into the wall, the kind that forms a huge switch with which someone might start a very great machine. September could just barely see the ornate handle in the dark. It made her think of the one that, when flipped, animated Frankenstein’s monster in the film her mother quite regretted taking her to. For a week afterward, September had run about the house, turning on the lights in every room and booming out what she considered a very scientific and professional cackle.

September threw the switch. She could hardly have done otherwise—the handle invited her hand, carved delicately but with a real heft to the wood, as perfect and solid and enticing as if it had been made just for her. Some switches must be flipped, and some children cannot help turning off to on and on to off, just to see what will happen.

This is what happened:

The lights came on.

Fairyland-Below lit up at the bottom of the staircase like a field of fireflies: Streetlights flared; house-windows flushed ruddy and warm. A million glittering specks of light and sound flowed out as far as September could see and further, not one city, but many, and farms between them, a patchwork of rich, neatly divided lands. She stood as if on a cliff, surveying the whole of a nation. Above it all, a crystal globe hung down on its own huge, gnarled cable. The black, slippery rope disappeared up into a gentle, dewy mist. The great lamp glowed at half wax, a giant artificial moon that turned the silent underground blackness into a perpetual violet-silver twilight. On its crystalline face, a ghostly smokecolored Roman numeral glowed: XII.

September could no longer see the walls or ceiling of the cave, only sky and hills and solemn pearl-colored pine trees, as though this were the upper world, and the Fairyland she had known only a dream. Voices filled the silence as quickly as light had filled the dark, and bits of music, too: an accordion sputtering here, a horn sounding far off. Behind her, the long staircase wound up and up, vanishing away in the distance. Below her, only a few landings down, a pretty courtyard spread out, dotted with graceful statues and a little fountain gurgling inky water. She had not seen how close she was to the bottom in the dark! A park bench all of ancient bone perched invitingly next to the fountain, so that one might sit and look out at the view and have an agreeable lunch.

And off in the corner of the courtyard, rather poorly hidden by a statue of a jester juggling little jeweled planets with rings of copper and brass, stood a very familiar shape. A shape with wings, and an extremely long tail, and great hindlegs, but no forelegs.

“Ell!” September cried, and her heart ran all the way down the steps ahead of her, around and around, until she could barrel across the courtyard and throw her arms around the Wyverary’s thick, scaly neck.

We may forgive her for not seeing it right away. In the gentle twilight of the crystal moon, many things look dark and indistinct. And September was so terribly glad to discover her friend waiting for her after all that she clung to him for a long time without opening her eyes, relief flooding through her like a sudden summer rainstorm. But eventually she did open her eyes, and step back, and realize the truth of it: The creature she hugged so fiercely was not A-Through-L, her beloved Wyverary, but his shadow.

“Hello, September,” said Ell’s shadow, gently, shyly, the rough, happy baroom of his voice soft and humble, as if certain that any moment he would be scolded. He seemed solid enough when she hugged him, but his skin no longer gleamed scarlet and orange. It rippled in shades of black and violet and blue, shimmering and moving together the way a shadow does when it is cast upon deep water. His eyes glowed kindly in the gloam, dark and soft and unsure.

“Oh, September, you mustn’t look at me like that,” he sighed. “I know I am not your Ell—I haven’t big blue eyes or a fiery orange stripe on my chest. I haven’t a smile that just makes you want to hug me. But I have been your Ell’s shadow all his life. I lay there on the grass below him when you met, and on the Briary grounds when we found Saturday in his cage, and on the muffin-streets in the Autumn Provinces when you got so sick. I worried with him for you. I lay on the cold stones in the Lonely Gaol, and I was there at the end when you rescued us. I have always been there, and I love you just the same as he did. My father was a Library’s shadow, and I also know all the things that begin with A-Through-L. I could be just as good to you as he was, if you can overlook the fact that I am not really him at all, which I admit is a hurdle.”

September stared at him, how he ducked his head so shyly and seemed almost frightened of her. If she frowned at him she thought he might actually run away. She wanted to think this was her Wyvern. She wanted him to be A-Through-L, so she could stop feeling so alone. But when she tried to hold out her hand to him once more, she found she could not quite. “Where is Ell, then?”

“In the Civic Library of Broceliande, I expect. He’s, or, well, we’ve got an internship and a Studying Curse from Abecedaria, the Catalogue Imp. After you left, we, well, he felt it’d be best to perform a few Literary and Typographical Quests before presenting himself to the Municipal Library of Fairyland. Even the Civic Library spoke gruffly to him, for Libraries can get very stuck in their ways and hostile to new folk, especially when new folk breathe fire at the Special Collections. But we got a lunch break every day and read the new editions before anyone. We were happy, though we missed you with a fierceness. We kept a file of wonderful objects and happenings called Things to Show September When She Gets Back. But one day when we were shelving the new A. Amblygonite Workbook of Queer Physicks, Vermillion Edition, which has to go quite high up so little ones won’t get ahold of it and make trouble, I fell off of myself. Of him. Of A-Through-L. Pronouns are a tough nut when there are two of you! I can’t describe it better. It didn’t hurt; I felt a strong sucking, as though a drain had opened up in my chest. One moment I was in the Library, the next I was half flying and half tumbling head over tail above the cities down here, and many other shadows fell after me, like black rain.”

The shadow-Ell shifted from one violet foot to the other.

“At first, I was very upset. I’d lived with my brother since we were born! What would I do without him? I only knew how to stomp when he stomped, sing when he sang, roast shadow-apples with my gloomy breath when he roasted real ones with his flame. Do you see? Even I thought of him as real, and me as false. My wings, my scales, my apples—I didn’t even know how to say mine back then! Everything was his. Well, that’s not right at all. I’m talking to you. I am an A-Through-L, even if I am not the A-Through-L. And who is to say I am not the A-Through-L, and he my shadow—if a rather solid and scarlet-colored one? That’s what Halloween says, anyway. Shadow Physicks are fearfully complicated. A. Amblygonite has no idea. When I finally landed safely down here, I found I was solid, and hungry, and ready to turn flips in the air of my own making! Ready to do my own sorts of magic! Ready to stand on my head if I liked, and speak without him speaking first! I was so happy, September. I cried a little, I’m not ashamed to say. And Halloween said, ‘Be your own body. I’ve vanished your chains, just like that! Jump and dance if you want. Bite and bellow if you want. You are free beasts.’”

September winced. She did not want to ask. She knew already. “Who is Halloween?” she whispered.

Shadow-Ell uncoiled his neck and turned in a circle, dancing a strange umbral dance. “Halloween, the Hollow Queen, Princess of Doing What You Please, and Night’s Best Girl.” The Wyverary stopped. “Why, she’s you, September. The shadow the Glashtyn took down below. She says when the parties are, and how to ride them true.”

September pressed her lips together. It is very hard to know what to do when your shadow has gotten loose in the world. Just think, if another version of you, who had not really listened when your parents tried to teach you things, or when you were punished, or when the rules were read out, decided to run off and take a holiday from being sweet and caring about anything at all? What could you possibly say to your wilder and more wicked self, to make your wanton half behave?

“Where do I live?” September said uncertainly. “I would like to talk to myself.”

Ell scrunched up his blue-black muzzle. His silvery whiskers quivered. “Well, she’s not your self anymore, you see. That’s the point. But she lives in Tain, which is the shadow of Pandemonium, in the Trefoil, which is the shadow of the Briary, all of which is right under the MoonBelow. But really, she’s so busy, September! She’s hasn’t got a moment for visitors. There’s a Revel tonight, and she’s hardly got a dress picked out, let alone balloons enough for all.”

“What’s a Revel?”

Ell smiled, and it was quite unlike any other smile September had seen on Ell’s dear, sweet face. The smile curved across his muzzle and his silver whiskers: sly and mysterious and secret. The kind of smile that has kept a froggy, dark sort of surprise in its back pocket, and won’t spoil it too soon.

“You’ll love it. It’s just the very best thing,” Ell said, and corkscrewed up his tail in delight, letting it uncoil languorously around September. Finally, this old, familiar gesture was too much for her. Perhaps she ought to have been more guarded and careful, but she missed her Wyverary so. She missed him being hers. She missed being his. And so she let the great violet swirling tail enfold her and gave it a great hug, shutting her eyes against Ell’s skin. He smelled like Ell. He looked like Ell, apart from the deep patterns of lavender and electric turquoise turning under his onyx skin. He knew everything Ell knew. That had to be good enough. What was a person, if not the things they knew and the face they wore?

“Let us go and do magic, September!” The Wyverary suddenly crowed, nearly howling up at the crystal moon with gladness that she had hugged him at last and not sent him away. “It’s such fun. I could never do it before! Apart from fire-breathing and book-sorting. And later you will come to the Revel, and wear the spangliest dress, and eat the spangliest trifles, and dance with a dashing Dwarf!”

September laughed a little. “Oh, Ell, I’ve never seen you like this!”

The shadow of A-Through-L grew serious. He dropped his kind face down next to hers. “It’s what comes of being Free, September. Free begins with F, and I am it. I like spangles, and I like to dance and fly and have Wild Doings, and I do not ever want to go to bed again, just because a great lug attached to me has gone to bed. I shall Stay Up forever!”

September twisted her hands. “But I can’t go to Revels and do frivolous magic! I’ve come to clean up my mess and restore Fairyland’s shadows, and that’s all. After it’s done, I shall go right back Above and put in a request for a proper Adventure, the kind with unicorns and big feasts at the end. I didn’t know you’d be here, and I’m glad for you, because you seem to be very happy about being your own Beast, but it doesn’t mean I can let Halloween keep on taking things that aren’t hers.”

Ell’s eyes narrowed a little. “Well, they aren’t yours, either. And anyway, don’t you want to see Saturday and Gleam? I thought you loved them. Not a very good love, that only grows in sunshine. And if, on the way, we happened to trip and stumble and just accidentally fall into magic, well, who could blame you? Come on, September. You didn’t used to be such a pinched little spinster about everything.”

September opened her mouth a little. She felt as though the Wyverary had actually stung her, and the slow poison of it spread coldly under her skin.

“You didn’t used to be cruel,” she snapped back.

A-Through-L’s eyes grew wide, and he shook his head vigorously, as if he were a shaggy dog shaking off water. “Was I cruel? Oh, I didn’t mean to be! Only I’m not used to being the one who talks! The other Ell took care of all that, and he was so good at it—why, he made friends with you in just an instant, without really even trying, that’s how sweet and clever and good at talking he is! I would have made a bumble of it, and you would have found some burly old Dragon with four proper limbs to have Adventures with. And now I have bumbled it! And you’ll never think I’m handsome or wise or worthy of walking about with you. I am wretched. I am woe! Those begin with W, but today I know what they mean, and they mean Hurting; they mean Gloomy and Disconsolate!” Huge orange tears spilled from the beast’s eyes like drops of fire.

A curious thing happened inside September, but she did not know its kind. Like a branch that seems one day to be bare and hard, and the next explodes with green buds and pink blossoms, her heart, which as we have said was very new and still growing, put out a long tendril of dark flowers. Hearts are such difficult creatures, which is why children are spared the trouble of them. But September was very nearly not a child anymore, and a heaviness pulled at her chest when she saw the poor shadow quivering with distress. Hearts set about finding other hearts the moment they are born, and between them, they weave nets so frightfully strong and tight that you end up bound forever in hopeless knots, even to the shadow of a beast you knew and loved long ago.

September reached into her red coat and drew out her ration book. The coat did not quite want to let it go, and pulled on her hands as she plucked it out, but September prevailed. She showed it, reluctantly, to Ell.

“I know your magic would be a sight to see, and if I had a ration to spare I’d put it on the barrelhead . . . only I don’t, Ell. I mustn’t squander! I’ve resolved not to squander. If you eat up all your sugar today, what will you do when your birthday comes around? And there’s nothing wrong with spinsters, anyway. They have nice cats and little bowls full of candy. Mrs. Bailey and Mrs. Newitz are the kindest ladies you’ll ever meet, and they have nips of whiskey in their tea like cowboys.”

Ell swore he would never call her names of any sort, but sniffed curiously at her ration book. A rather sullen-looking King Crunchcrab peered out from the front, holding a shield emblazoned with two crabs joining claws over a glittering jeweled hammer.

“But you don’t need that here, September. Why would you need it? That’s the whole point, isn’t it?”

A-Through-L’s beautiful shadow leapt up and spun around so fast he seemed a great black blanket thrown up into the air. He bent down like a bull, pawed the earth, and bolted—running around September in three quick, dark, tight circles. A crackle shivered up around her; all the hairs on her skin stood on end. She had the thick, swollen, hardening sensation of her whole body falling asleep like an arm or a hand. Strange fiery lights flickered around her, glittering and dancing and darting at abrupt angles. Ell skidded to a stop, his face lit with rapture and mischief and high humor.

And suddenly September was not September anymore, but a handsome Wyvern of middling size, a bright fur ruff around her neck where her red coat had been, her skin flushing a shade of deep, warm, flaming orange from whiskers to tail.

A Wyvern’s body is different from the body of a young girl in several major respects. First, it has wings, which most young girls do not (there are exceptions). Second, it has a very long, thick tail, which some young girls may have, but those who find themselves so lucky keep them well hidden. Let us just say, there is a reason some ladies wore bustles in times gone by! Third, it weighs about as much as a tugboat carrying several horses and at least one boulder. There are girls who weigh that much, but as a rule, they are likely to be frost giants. Do not trouble such folk with asking after the time or why their shoes do not fit so well.

September quite suddenly found herself with all of these things: the tail, the wings, the tremendous weight. In addition to all that, she had a fetching ridge of white-gold plates along her back, which female Wyverns possess but males do not. At first, September nearly tipped over. Then she felt horribly dizzy, then queasy, and finally gagged miserably, fully expecting to throw up.

Green fire bubbled out of her mouth in a neat circle.

This, however, seemed to sort out the quarrel her equilibrium was having with what we might call her sense of September: that feeling of personal permanence most of us enjoy, knowing that our bodies and ourselves are on roughly speaking terms, have come to grudgingly understand each other, and that we are very unlikely to turn into a wombat or large bear anytime soon.

Her squat hind legs said to her wings, I am a Wyvern now. Her tail said to her spine-ridge: No use complaining. Her whole being swelled up like a great orange-and-gold balloon to say the next most logical thing: I can fly.

All thought of shadows and Revels and rations fled from September as she took a heaping, thundering start: one step, two, three, and up, up! Her great pumpkin-colored wings, veined with delicate green swirls, opened out and caught the air, flapping as naturally as her legs had ever walked. The night-wind of the underworld buffeted her beet-bright whiskers. September’s enormous, seven-chambered Wyvern heart boomed deep in the depths of her chest. Flight was not a thing she did, it was a thing happening inside her, a thing thrilling through her reptile blood and her armored skin, a thing jumping in her bones and reaching up to catch the heels of the air. The crystal moon shone down warmly on her scales—the ceiling of the world seemed so terribly high, even when she turned huge, lazy circles around clusters of hanging stars. Up close, she could see the stars were jewels, too, with sharp prongs like shards of ice. The difference between a ceiling and a sky was only where you stood. September wanted to shoot up to the very top, bash through the earth, and erupt like a giant fiery mountain into the blue Fairyland air.

She might have done it, too, but A-Through-L sailed up underneath her, easily flying on his back, his indigo belly turned up toward her.

“Natural flier!” he harroomed. “Try a flip!”

And below September, the Wyverary executed a gorgeous backward somersault, spraying a nearby star with an arc of dancing emerald flame as he did. September laughed and her laugh sounded like a roar; as if she had never been able to properly laugh in her whole life, only giggle or chuckle or grin, and now that she could do it right, now that her laughing had grown up and put bells on, it had become the most boisterous, rowdy roar you ever heard. She pitched forward and thought for a moment she might lose altitude and fall, but her body knew its paces. Her wings folded tight as she turned over and flared open again as she came upright. September roared again, just for the big, round joy of it.

“It’s all so small from up here, Ell!” she cried, and her cry had gotten deep in the baritone range, such a rich, chocolatey voice she thought she might talk forever just to hear herself. “How can Fairyland-Below be so big? It must be quite as grand and huge as Fairyland itself—maybe bigger, even!”

A-Through-L turned a slow spiral in the air as they dodged stars on wires and looked down on the star-map of cities below them. Still, September could not even see stone overhead that would mark the end of the underground kingdom—only mist and gloam. The Sibyl’s staircase must have been in a shallow part of the world, for the rest of it was as deep as the sea and twice as full of life.

“Ever seen a mushroom?” Ell said, flexing his shadowy claws.

“Of course!”

“No, you haven’t. You’ve seen a little polka-dotted cap or an oystery bit of fungusy lace. What a mushroom is, what it really looks like, is a whole mad tangle of stuff spreading underground for miles and miles, tendrils and whorls and loops of stem and mold and spore. Well, Fairyland-Below isn’t separate from Fairyland at all. It is our cap. Underneath, we grow forever secretly outward, tangling in complicated loops, while what you see in the forest is really little more than a nose poking out.”

Somehow, a thought squeezed through the radiant shriek of flight in September’s veins. She stopped short in the air, pumping away with her fat saffron feet, four claws clutching at the night.

“Why didn’t you have to use a magic ration? Why can you do this? Ell can’t do this—he would have, if he could have. We had to walk so far! Tell me you have been studying hard and have gotten a diploma from a Turning-Girls-into-Things school. Tell me I have not tasted something wicked by letting you change me—I do not want it to be wicked! I want to feel like this always!”

A-Through-L’s face made a complicated expression. It looked shamed, then thought better of it and looked proud, then cunning, then filled up with so much love that all the other quirks of his mouth and angles of his brow smoothed together into one beaming, jubilant frown.

“We’re the mushroom, September. Why would we ever need to ration magic down here? Shadows are where magic comes from. Your dark and dancing self, slipping behind and ahead and around, never quite looking at the sun. Fairyland-Below is the shadow of Fairyland, and this is where magic gets born and grows up and sows its oats before coming out into the world. The body does the living; the shadow does the dreaming. Before Halloween, we lived in the upper world, where the light makes us insubstantial, thin, scraps of thought and shade. We weren’t unhappy—we made good magic for the world, sportsmanlike stuff. We reflected our bodies’ deeds, and when our brothers and sisters went to sleep, we had our own pretty lives, our shadow loves, our shadow markets, our shadow races. But we had no idea, no idea how it could be under the world with our Hollow Queen. And now we shall never go back. The more shadows join us in the deep, the more our cities get soaked in magic, just sopping with it, and you don’t even need a book of spells or a wand or a fancy hat. Just want something bad enough, and run toward it fast enough. The rations are for Above-Grounders. They can’t have it without us, and they’ve been drinking from our hands for far too long.”

September’s huge jaw hung open. Her red whiskers floated beautifully on the cave-winds. And in a moment, as fast as it had happened, her Wyvern-body vanished. She fell, tumbling through the sky—only to land softly on A-Through-L’s broad belly. He held her gently with his hind legs. September cried out miserably—her body had gotten small again, like a dress that has shrunk in the laundry. Her skin felt so tight she would surely die of tininess. Her bones groaned with loss, with longing to fly once more.

“It doesn’t last long,” Ell admitted. “Not yet.”

After a long while of feeling sorry for herself and worrying over what the Wyverary had said, September whispered, “If Fairyland-Below is Fairyland’s shadow, what is the shadow of Fairyland-Below? What’s under the underworld?”

Ell laughed like thunder rolling somewhere far off. “I’m afraid it’s underworlds all the way down, my dearest, darling flying ace.”

Now, just as there are important Rules in Fairyland, there are Rules in Fairyland-Below, and I feel I must take a moment to curtsy in their direction. These are not the sorts of Rules that get posted in front of courthouses or municipal pools. For example, underworlds, on the whole, encourage roughhousing, speeding faster than twenty-five miles per hour, splashing and diving. Unattended children, dogs, cats, and other familiars are quite welcome. And if September had come underground at any other time, she might have seen handsome, clearly lettered signs at every crossroad and major landmark kindly letting visitors know how they ought to behave. But she came underground at just the exact time that she did, and Halloween had had all those friendly, black-andviolet-colored signs knocked down and burned up in a great fire, which she danced around, giggling and singing. Halloween felt it quite logical that if you destroy the rule-posting, you destroy the rules. The Hollow Queen hated rules, and wanted to bite them all over.

But some Rules are immutable. That is an old word, and it means this cannot be changed.

Thus, both September and Halloween did not know something on the day our heroine entered Fairyland-Below. September did not know the Rules, and Halloween did not know that the Rules still ran on like a motor left idling, just waiting to roar into motion.

I am a sly narrator, and I shall not give up the secret.

The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There © Catherynne M. Valente 2012